With a career spanning more than 70 years, John Lounsbury was known as a teacher, writer, editor, mentor, and advocate for the development of schools and educators.

Dr. Lounsbury was also well known as a Legacy Leader in the middle school movement that began in the early 1960s. In particular, he served as an advocate for exemplary middle grades practices that support the development of teacher–student relationships, such as schools-within-a-school and looping.

*Information about Dr. Lounsbury was adapted from John H. Lounsbury: Middle School Mentor to All (Association for Middle Level Education, 2019).

The Early Years

The Early Years

John Horton Lounsbury, reportedly named after John Horton, captain of the good ship Swallow that followed the Mayflower to American shores, was born in Brooklyn, New York on January 1, 1924. His mother, Elsa Mae Cook Lounsbury, had gone to a doctor in Brooklyn because she experienced difficulties during her pregnancy; consequently, John was delivered in a Brooklyn hospital. Except for his first five days in that Brooklyn hospital, John grew up in Plainfield. He began life in a financially stable household. His father, equipped with just a high school education, became successful in the investment world of Wall Street with a position at the well-established Kidder-Peabody Company.

In 1932, the Lounsbury household moved to a different Plainfield neighborhood. This involved changing schools for young John and his siblings. In his first elementary school, John had been promoted to first grade during the middle of his kindergarten year. He was reading well before his classmates, likely due to his mother’s animated readings of books to him as well as his father’s love of learning. Mr. Lounsbury often read poetry at the dinner table – Emily Dickinson was his favorite. He also, with a dramatic flair, would recount the full tale of Rudyard Kipling’s Gunga Din. The last line is one that, to this day, John remembers: “You’re a better man than I am, Gunga Din!”

In the summers before and after senior year in high school, John worked at a tire retreading shop and parking garage. Commuters parked their cars at the garage while they went to work in New York City. John, when not busy with the hot and dirty retreading work, washed the parked cars in the hope that their owners might notice and give him a quarter. Later, after he got his driver’s license, John drove the shop truck and delivered tires all over central Jersey, again a job he particularly enjoyed.

During his high school years, John developed leadership skills while participating in the YMCA sponsored Leadership Club. The young men, in uniforms, participated in body strengthening activities such as swimming, working out on the parallel bars, the rings, and the high bar. The club also provided sessions on leadership and personal development which were led by the club’s adult sponsors.

One high point of Lounsbury’s high school education was a biology course he took during his senior year. Doc Hubbard, the teacher, had a quiet, dignified, demeanor and made biology come alive. John earned an A in this class, the only one he received during his entire high school career.

In the fall of 1941, Jersey Boy John enrolled in Tusculum College, way down South. On December 7, 1941, when news broke of the Pearl Harbor attack, John soon joined ASTP (Army Specialized Training Program), which permitted him to stay in college a second year. At the end of his second year at Tusculum, John returned—by Greyhound bus—to New Jersey and reported for active duty at Ft. Dix, N.J.

Private Lounsbury boarded a troop train, the first of many he would ride, and headed to California for basic training in the infantry at Camp Roberts. This was a rigorous, physically demanding period that also included the infamous task of peeling potatoes while on KP (kitchen patrol) duty. John, as was his nature, took it all in stride.

The Formative Years

The Formative Years

With two years of higher education under his belt, Lounsbury knew he wanted go back and finish college after his discharge. While in the army, Lounsbury spent hours wrestling with the idea of his life’s vocation. He had taken a correspondence course on operating a business, but he eventually realized that was not what he wanted to do. Teaching as a career had never occurred to Lounsbury, but Dr. Johnson of Stetson University, perhaps with a bit of insight, scheduled John for a course titled History of Education. In that course, taught by the distinguished Dr. Boyce Fowler Ezell, John realized that teaching was indeed what he really wanted to do with his life. Reflecting on his experiences in the war made him understand that he was more interested in people than he was in bugs and butterflies. With a new sense of purpose, John discovered that his studies engaged him. John made all A’s, even an A+ in one course, a significant change from his checkered high school days.

The Stetson teacher preparation program was typical for that era in that it limited field experiences to student teaching in the last year of study. Lounsbury, never having set foot in a public school since his high school graduation, went out to do his student teaching at Deland Junior High School the semester before graduation. Since he had considerable credits in biology, he did his student teaching in eighth grade biology, even though he now was a social studies major. Dr. Randolph Carter, who taught Lounsbury and became his advisor at Stetson, saw real promise in John. He urged him to continue his education at George Peabody College for Teachers in Nashville, Tennessee.

At Peabody, John enrolled in a course taught by Dr. Louis Armstrong, a dynamic professor who encouraged John to think about the philosophical aspects of education, asking the important “why” and “for what ends” questions. Dr. Armstrong was passionate about practicing democracy in the classroom, and this resonated with John, who began to form a personal philosophy of education. Courses in Sociology and Geography were interspersed with courses in Curriculum, Human Growth and Development, Social Studies Education, and the like. John completed his Master’s Degree in the summer of 1948, majoring in secondary curriculum and instruction.

After graduating from Peabody, John received an unexpected phone call from the principal of New Hanover High School in Wilmington, North Carolina. He had read John’s placement papers, or resume—John was offered, and accepted, a position to teach World History to ninth graders and Government to seniors at this large and highly regarded high school. Lounsbury truly enjoyed the seniors he taught, but he was frustrated with the routines of teaching government classes by the requirement to follow Magruder’s American Government textbook. John initiated a unique alternative. He continued to teach as he was expected to do, expanding on and discussing the textbook, chapter by chapter, four days a week. However, on the fifth day, Friday, classes were turned over to the students, who organized themselves into what might be called civics clubs. They elected officers and carried out various learning activities that they planned. Some activities initiated by the students included debates on topics such as “Corporal Punishment” and “Should 18-Year-Olds Be Allowed to Vote,” surveys of the knowledge citizens had about their government and its officials, and speaking invitations to local officials from the police department and F.B.I.

Lounsbury was promoted to Social Studies Department Chair in his second year. Then, two years later, he was appointed Secondary Supervisor. It was through this position that Lounsbury became involved with the junior high school and, ultimately, the middle school and what we know today as the middle level education movement.

Higher Education Beckons

Higher Education Beckons

Following the close of his third year teaching at New Hanover High School, Lounsbury returned to Peabody for the 1952 summer session. Peabody had become known as “the Columbia of the South,” and as a result attracted several distinguished faculty. John enjoyed classes with several of these special faculty such as Dr. William Van Til, a well-known writer and progressive educator who had earlier been a core teacher at the famous Ohio State University Laboratory School and Harold Benjamin, famous for “The Saber-Tooth Curriculum.”

In connection with his classes, John delved into the works of Herbert Spencer, John Dewey, William Heard Kilpatrick, George Counts, and Carl Rogers, among other noted educators. The humaneness of those thinkers and his Peabody professors, all of whom emphasized the value of the individual with a commitment to help that individual fulfill his/her potential, struck a chord with John; his personal values became aligned with the progressive view of education to which he was exposed at Peabody and by the writings of these distinguished thinkers. As a result, John’s educational philosophy was forged that summer, and remained unchanged throughout his career. And that philosophy deepened as John developed associations with other contemporary thinkers and leaders and encountered opportunities to engage in various activities and events where that philosophy would come into play.

John described his view of progressive education this way: “Progressive education, middle level education, same thing—basing educational experiences on what we know about learning and society and the nature of kids. They’re the enduring triangle, the enduring foundations, and they’re always present.”

One of Lounsbury’s assignments when he was appointed Secondary Supervisor in the New Hanover County School District was to plan the conversion of two elementary schools into two junior high schools. He knew almost nothing about junior high schools, as such, so he began visiting the seventh and eighth graders enrolled in these elementary schools. He found them to be most interesting, eager to learn and curious, more so it seemed than high school students in general. When he went back to Peabody for the summer, John was intent on gaining an understanding of this intriguing age group and the whole junior high school concept. While in Nashville, he visited junior high schools in Davidson County; later he was able to observe Gordon Vars’ eighth grade class at the Peabody Demonstration School. Through these experiences Lounsbury developed a genuine affinity for young adolescents. A specialized focus in his career had emerged.

ChatGPT said:

After John enrolled in another course with Dr. Van Til, who had grown impressed with his work, Van Til pulled him aside to discuss his future in the doctoral program. What followed were the 1952-1954 school years of full-time residence, two very significant years of learning, growing, and development for John, both as an educator and as a person. John’s completed dissertation, titled The Role and Function of the Junior High School, ran well over 300 pages, with a substantial number of figures and tables included. William T. Gruhn and Harl R. Douglass, co-authors of The Modern Junior High, were also influential in Lounsbury’s understanding of what junior high education should and could be. Subsequently, John developed an association with both men and became a co-author with Douglass on two articles reporting on a small study these two scholars conducted.

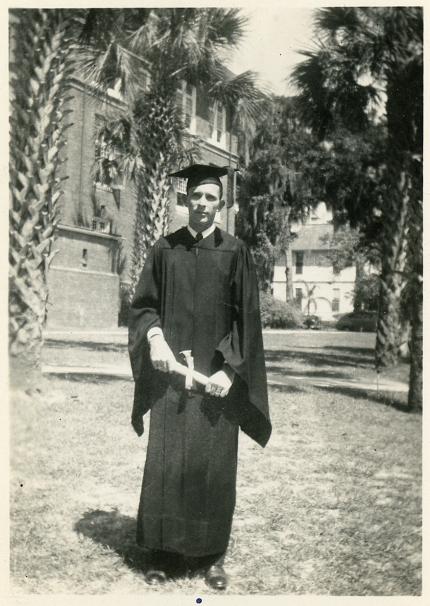

Graduation for Lounsbury was truly the commencement of a new phase of life, one that would involve further learning, research, writing, speaking, service in professional associations, and administrative leadership. Leaving Nashville with an Ed.D. diploma in hand, John moved to Berry College, outside of Rome, Georgia, where he had been recruited to become Chairman of the Division of Education, a position for which he really was not prepared, either by experience or by formal study of administration.

After a two year stint at Berry College, John secured a position at the University of Florida in Gainesville as an assistant professor. At the University of Florida, John became the social studies education specialist, teaching a related methods course, a general curriculum course, and supervising student teachers in their field placements throughout central Florida. He became active among Florida social studies educators and founded the Florida Council for Social Studies along with Dick Skretting of Florida State University.

Every year while in Florida, Lounsbury was actively pursued by his former colleague from Berry College, Dr. Robert E. “Buzz” Lee, who had become president of the Women’s College of Georgia (now Georgia College and State University). Finally, in 1960, John relented and resigned his position at Florida. He considered his work in Florida to have been productive, and satisfying. Although he was somewhat reluctant to leave, John accepted the offer to become Chairman of the Division of Teacher Education and Director of the Graduate Program at the Women’s College of Georgia in Milledgeville.

Leadership in Teacher Preparation—A Reluctant Dean

Leadership in Teacher Preparation—A Reluctant Dean

During these early years in Milledgeville, John spent some time in promoting best educational practices for young adolescents in junior high schools. His professional writings at this time also dealt with the junior high school. Published in 1960 in Educational Leadership “How the Junior High School Came to Be” was a very well received article that was reprinted in several other books. Another article, “Junior High School Education—Renaissance and Reformation,” was published in the High School Journal. Harl Douglass joined John in a research study that resulted in two articles in the middle of the decade; “Recent trends in junior high school practices 1954-1964” appeared in the NASSP Bulletin in 1965; “A decade of changes in junior high practices” was published in Clearing House in 1969.

John’s long-held beliefs about student-centered democratic education being the best way to meet the needs of young adolescents were, at that time, applied to the junior high. But the same ideals, the same characteristics, continued to be paramount when they were applied to the emerging middle school. Lounsbury often said, “There isn’t a dime’s worth of difference between the junior high concept as advanced by founders Leonard Koos and Thomas Briggs and the middle school concept as advanced by William Alexander and others.” There was a great difference, however, between the junior high that had, unfortunately, become operational and the middle school ideal being advanced in current talks and articles. This was a reality almost never recognized. The junior high school vs. the middle school battle that was widely waged should never have begun, for they were not conflicting theories.

Lounsbury’s prime attention at this time was, however, correctly given to the development and improvement of the college’s teacher education and graduate programs. Responding to the interest in graduate level teacher preparation that was evident throughout the nation, the Women’s College of Georgia (renamed Georgia College and State University in 1996) established a fifth-year certification program that resulted in an M. Ed. degree. Recipients would be eligible for the new salary scale step established by the Georgia State Board of Education. As a result, educators throughout middle Georgia were quick to initiate graduate work. Summer school in Milledgeville became a mecca for teachers anxious to achieve advanced professional preparation and a raise in salary. Late afternoon and evening graduate classes were offered to meet the demand for graduate study. Part-time faculty members were needed to staff some of these courses. Excellent, highly qualified candidates, most with Ph.D.’s, were available. These part-time faculty members enriched the GSCU program.

John always carried some teaching responsibilities as a part of his schedule. He especially enjoyed teaching Introduction to Education, because through it he believed he could help students develop positive attitudes toward teaching and begin to view themselves as teachers. In this foundational education class, John used literature to foster an understanding of teaching apart from the institutionalized version of education typical at the time and to aid students in realizing the profound influence teachers can have on their students. John’s charges read books like Jesse Stuart’s The Thread that Runs So True, Anna and the King of Siam (The King and I) by Margaret Landon, and Windows for a Crown Prince by Elizabeth Gray Vinings to get a sense of the power that teachers could exercise. Students also read extensively in professional journals; textbooks were not used.

Another teaching strategy Lounsbury used was the posting of thought-provoking quotations. On half of a poster board John would print, in very large script, a quote. Three examples of the pithy statements he used were: “The unexamined life is not worth living” (Socrates), “He knows not England, who only England knows” (Kipling), and “Babies of all nations are alike until adults teach them” (Applegate). John posted a quote prior to class and usually made no comment about it when class commenced. Eventually a student would bring it up; a lively discussion often ensued.

Always prepared for class, John typically began by recalling the material that had been discussed the previous day. Probing, provocative questions punctuated the presentation of information and discussion that followed. Field assignments had students assisting in classrooms, interviewing teachers, and working with students in afterschool activities.

John became active in Georgia state level meetings and education committees, early and often. He and Mary Compton, professor of Curriculum and Instruction University of Georgia and fellow middle level advocate, appeared before the State Board of Education on two occasions, pushing for distinctive certification for the middle school years. They were ultimately successful in making Georgia the second state in the USA to achieve this important reform. (Ken McEwin, along with other North Carolina educators, had led the Tar Heel State in becoming one of the first to put in place a distinctive middle grades certificate.) In 1975, John was appointed to the Georgia Legislator’s Curriculum Study Committee; he was also selected to be a part of the State Task Force on Teacher Education, 1982-84. In 1989, John invited key leaders from all the teacher preparation institutions in the state to the GCSU campus and established a new association, the Georgia Professors of Middle Level Education. Though slow initially to gain support, before long this group became well-established and emerged as a strong national group (NaPOMLE) and an affiliate of NMSA (now AMLE).

The rapid growth of undergraduate and graduate programs at GCSU made the old Education Building inadequate. John and the president led efforts to secure a new facility for teacher education. A multi-year project of the Board of Regents culminated in the opening of the William Heard Kilpatrick Education Center in 1976. This facility combined the former Peabody Laboratory School with new construction to provide a fully modern, air-conditioned building. With the approval by the Regents of John’s request, the facility was named for William Heard Kilpatrick, Georgia native and internationally recognized educational philosopher, and friend of Guy Wells, a former Georgia College President. At the formal dedication ceremony, Kilpatrick’s only surviving child, Margaret Louise Kilpatrick Baumeister, and his grandson, Heard Baumeister, were present.

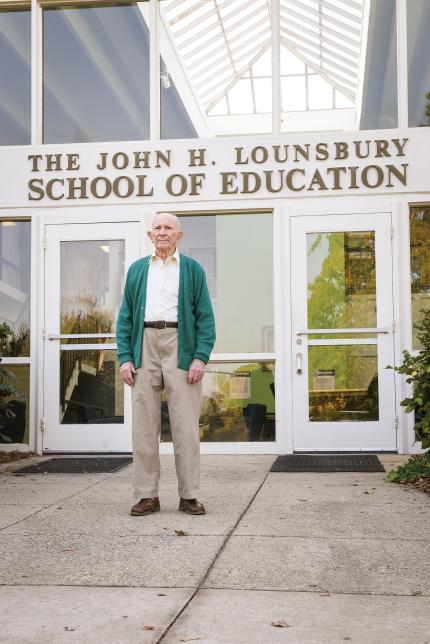

In 1997, fourteen years after his retirement, a group of faculty members, some retired, appeared in John’s office to report that their petition to rename the School of Education after John had been approved by the Board of Regents. A dedication ceremony was held in Peabody Auditorium with faculty and program participants garbed in academic regalia and accompanied in the processional by bagpipes. The president, vice president, a faculty member who had been a student of John, and Sue Swaim (NMSA’s Executive Director) all spoke at this historic event. The surprise recognition for John’s work as dean, and his continued accomplishments in the role of NMSA Publications Editor and middle level advocate, both honored and humbled him.

The Dean Retires—The Man Does Not!

The Dean Retires—The Man Does Not!

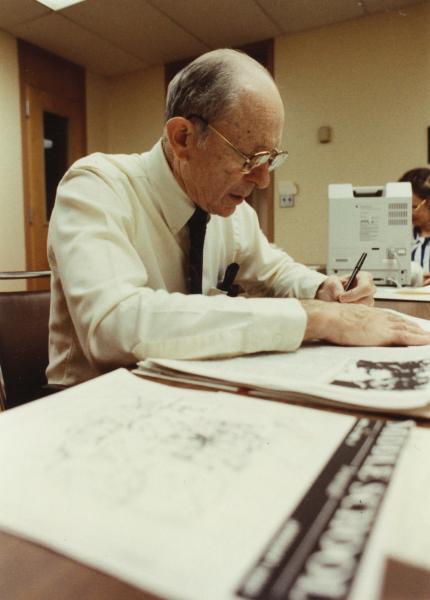

When John retired from Georgia College in October 1983, it was a foregone conclusion that he and NMSA publications would be provided an office on campus. The continuance of his on-going associations, both formal and informal, with students and faculty was a certainty. Georgia College was glad to house the Publications Office of a major professional association, for the college’s name and reputation was carried far and wide via John’s travels, correspondences and publications. In addition, John took on a role in Georgia College’s athletic affairs, keeping the scorebook at basketball games and traveling with the team.

The 1980s and 1990s comprised what has been characterized as the heyday of professional development activities. The extensive and widespread in-service activities promoting the middle level in these years were truly remarkable. John became a popular spokesperson for NMSA and its mission through presentations at professional development events, affiliate conferences, consultations, and institutions. His articulation of the middle level mission delivered with passion, zeal, and clarity of thought was well received. His travel schedule was astounding as he crisscrossed the country speaking at conferences and various professional development events.

On multiple occasions John was asked to be the speaker for dedications of schools or celebrations of awards given. NMSA named its highest award after him, and he introduced nearly all of the John H. Lounsbury Award winners honored by NMSA until he retired. A gifted orator, John captivated and motivated audiences with his carefully crafted word choice and deliberate delivery.

In 2002, the conference room and library at Oak Hill Middle School was dedicated to him. He received the Distinguished Service Award from the National Association of Secondary School Principals. He was a participant in the Lighthouse Schools to Watch program in Georgia. He was honored by the Baldwin County Retired Educators Association in 2013. Always a popular teacher, he received yearbook dedications at New Hanover High School, Berry College, Georgia College and GCSU's Early College.

With the death of Dr. John H. Lounsbury on April 2, 2020, the world lost a treasure. The world will remember Dr. Lounsbury as a Legacy Leader and one of the five Founding Fathers of the Middle Level movement.